OKAVANGO DELTA

Là où l'eau apprend à écouter

(Inspiré par l'encadré “Safari by water” de l'article sur le delta de l'Okavango de votre document).-compressé(1).pdf) [100_Dream_...ressed (1)]

La première chose que le Delta m'a apprise, c'est d'arrêter de parler.

Sur la carte, le Okavango On dirait que quelqu'un a renversé une rivière dans le désert et a oublié de balayer les morceaux. Sur l'eau, dans un mokoro bas, le temps s'arrête en prétendant qu'il se déplace en ligne droite. La proue soupire à travers les nénuphars et le monde se réduit au claquement des lèvres contre la coque, au balancement du papyrus, à la ponctuation précise d'un aigle pêcheur dans le ciel. “Nous ne parlons pas beaucoup ici”, a murmuré mon poler, Thero, en nous poussant dans un chenal vitreux avec le punt. “Nous écoutons. L'eau dit les choses avant les animaux. L'Okavango est, après tout, une safari par voie d'eau-Un laboratoire alimenté par les crues où les routes apparaissent et disparaissent, où les îles deviennent des péninsules et inversement, et où même les éléphants se mettent à nager lorsque cela semble être la chose la plus sensée au monde.-compressed(1).pdf) [100_Dream_...ressed (1)]

J'étais arrivé à bord d'un petit Cessna en provenance de Maun, cette ville où les chapeaux d'expédition étaient plus nombreux que les nuages et où chaque ligne de café comportait une observation chuchotée de léopard. La piste d'atterrissage n'était qu'un point de couleur havane dans une courtepointe verte. Un Land Cruiser m'a conduit au camp, les libellules faisant de l'autostop dans la poussière derrière nous, puis, après les présentations aux yeux écarquillés avec le personnel dont je me souviens encore des noms comme d'un accord - Neo, Kago, Thero -, nous nous sommes jetés à l'eau.

Premier jour : Déchiffrer la carte

Les canaux ont immédiatement commencé à me faire perdre le sens de l'orientation. Les cathédrales de papyrus ont repoussé le soleil ; les îles de sable ont dérivé à la limite de la vision, et les roseaux ont agi comme des chuchotements, tirant la conversation dans leur poche. Nous avons dérivé près d'un radeau de nénuphars, les soucoupes blanches retournées, les abeilles bavardant sur leurs barres de pollen. “Hippo”, a dit Thero - une question et un fait ; j'ai hoché la tête, le pouls faisant ce truc stupide de citadin. Le premier jet d'eau a ressemblé à l'expiration d'une planète, puis un autre, plus proche - les dos arrondis se sont gonflés, les yeux se sont levés comme des périscopes. “Respectez la section des barytons”, dit Thero en souriant, en nous donnant un coup de pouce. “Ils détiennent les droits de ces morceaux.”

Nous étions en route vers un camp plate-forme éloigné, situé entre les chacalberries et les leadwoods, une cabane dans les arbres où les passerelles se courbent comme le ferait une rivière si elle était en bois. Le déjeuner était composé de pap, de seswaa et de tomates qui avaient le goût d'avoir été apprises par une grand-mère très exigeante. Ensuite, un fan a cliqué comme le font les fans fidèles depuis des années. On fait la sieste dans le Delta comme si les rêves étaient une autre sorte de migration.

Soirée : Moremi's Low Light, High Drama

Au moment où nous avons traversé la lagune pour nous diriger vers la Réserve de chasse de Moremi La lumière était devenue cinématographique, la poussière capturant les rayons de soleil dans les hautes herbes et l'air suffisamment chaud pour faire frémir les pensées. C'est ici que Les éléphants nagent parfois-J'avais lu la phrase, souri à sa poésie ; maintenant, nous la regardions se dérouler - des troncs en tuba, des oreilles aplaties, un veau porté par deux vaches qui ne cessaient de jeter des coups d'œil en arrière comme pour dire : “Il va bien ; honnêtement, les humains, respirez.” Le Botswana réécrit ce que vous pensez savoir sur les éléphants. Vous ne vous contentez pas de les voir. Vous absorbez leur marée..pdf)-compressed(1).pdf) [100_Dream_...ressed (1)]

Nous nous sommes engagés dans un canal où les roseaux se sont séparés pour révéler des lechwe rouges marchant aussi délicatement que des ballerines, leurs sabots étant habiles à lire la boue. Un martin-pêcheur malachite s'est posé à un roseau de notre proue, concentré de couleurs et d'attitude. “L'eau rend tout le monde prudent”, disait Thero, “et la prudence rend tout le monde beau”. Il avait une façon de transformer les notes de terrain en psaumes.

De retour au camp, le dîner a dessiné une constellation de lanternes, et la nuit s'est mise à jouer son opéra : des hippopotames qui grognent, des insectes qui font la fête quelque part dans les arbres, une hyène qui joue son spectacle d'animal unique quelque part, pas assez loin. Je me suis allongé sous une moustiquaire, ce rideau de théâtre vaporeux entre moi et tout, en pensant que l'on peut venir dans un endroit comme celui-ci pour les animaux et être surpris lorsque les animaux sont là. silence devient le personnage principal.

Deuxième jour : Des empreintes de pas et un lion qu'on ne voit pas

A 5h15, le café arrive avec un “Dumela, rra”, et les stars n'ont pas encore pointé leur carte de pointage. “Nous allons marcher un peu, dit Neo, puis nous prendrons le bateau. Bottes aux pieds, nous nous engageons sur une route de sable qui fait semblant d'être droite sur une trentaine de mètres, puis s'enroule dans les virages. Le pistage est une autre façon d'écouter ; Neo a pointé des lignes et des hiéroglyphes dans la poussière : civette, steenbok, la hyène de la nuit dernière, un autre éléphant avec une empreinte plus petite et floue éraflant son ombre. Il m'a appris à remarquer la marge : les herbes pressées, la façon dont la rosée s'accroche à certaines extrémités de feuilles et pas à d'autres, la légère note aigre qui signifie qu'un troupeau de buffles est passé.

Nous n'avons jamais vu le lion dont les empreintes étaient parallèles aux nôtres sur une portion obstinée, mais c'était l'essentiel. “C'est le fait de ne pas voir qui vous permet de rester honnête”, a déclaré Neo. “Les gens viennent pour les observations. Les guides viennent pour les signes.” Je me suis senti à la fois humble et étrangement soulagé, comme si le monde avait eu la gentillesse de laisser certaines de ses pages non tournées pour plus tard.

Chaleur de midi : l'art de faire une chose à la fois

Le midi du Delta, c'est pour l'ombre. J'ai appris à être un animal qui ne fait qu'une chose : lire un paragraphe, boire une gorgée d'eau, regarder un gecko courtiser l'idée d'une fourmi errante, s'allonger et écouter un poisson claquer la surface d'un canal comme un tapis qu'on secoue. La tentation est grande d'empiler les expériences comme des souvenirs. Le cadeau consiste à laisser le temps se fondre en une longue heure bleue.

Après-midi : Quand l'eau décide de votre itinéraire

Un petit drame s'est joué à la fin : un troupeau de lechwe a regardé dans une direction suffisamment longtemps pour que nous finissions par le faire aussi, et que nous surprenions le léger frôlement de l'herbe sur les épaules d'un chat ; le guépard, ensuite - et le monde s'est rétréci à l'herbe rayée, à un bruissement, à l'idée de la vitesse qui fait chauffer son moteur. La poursuite n'a pas eu lieu. Peut-être que le chat n'avait pas bien calculé la distance, ou que le vent n'était pas porteur de la bonne rumeur. Mais nous avions été introduits clandestinement dans un moment qui ne nous devait rien.

Flotteur de nuit : Une lune sur l'eau

C'est Thero qui a eu l'idée de faire du bateau après le dîner. “Pas de lumière”, dit-il en regardant le ciel. “La lune suffit. Et c'était le cas. Nous avons glissé dans un monde lent et argenté, les lys fermant leurs bouches blanches pour la nuit, le papyrus faisant ce silence de papier, et une grenouille de roseau essayant son aria dans un coin près de mon genou. ”L'eau raconte les grandes histoires en douceur“, a dit Thero. ”On ne les entend que si l'on est resté silencieux pendant un certain temps.“

Troisième jour : Partir est un verbe qui a du poids

Le dernier matin, j'ai fait ce que l'on fait quand on aime un endroit : prétendre que l'on va juste faire une petite balade de plus. Une cigogne à bec selle a tourné la tête comme si nous avions dit quelque chose d'impoli ; un groupe d'hippopotames a rédigé un traité de paix avec notre sillage. Sur la piste d'atterrissage, une petite foule d'aigrettes blanches attendaient leur vol. Thero m'a serré dans ses bras comme le font les gens des rivières : étreinte, coup, distance. “La prochaine fois”, dit-il. “Peut-être plus haut dans l'eau. Peut-être plus bas. Mais ce sera la prochaine fois.”

Ce que l'Okavango vous apprend (que vous le demandiez ou non)

Vous pensez que vous allez chercher la liste des animaux sauvages. Vous restez pour la façon dont l'eau réorganise votre esprit, pour la façon dont silence devient quelque chose que l'on peut goûter, à la manière dont la main d'un guide sur une nouvelle gravure vous fait comprendre que la connaissance peut être douce. Vous revenez parce que les chaînes ne seront pas les mêmes, et parce que vous non plus.

Sagesse pratique que j'aurais aimé que quelqu'un murmure

Il est évident qu'il faut prévoir des couches légères, une écharpe pour le soleil et la poussière, des lunettes de soleil polarisantes, un sac de sport et un sac à dos. lampe frontale Laissez de la place pour ce qui est moins évident : la patience, le courage de s'ennuyer pendant vingt minutes pour qu'un martin-pêcheur puisse prouver que l'ennui est une erreur de diagnostic, des chaussures qui peuvent marcher dans la rosée comme dans la dignité. Acceptez que le Delta est une improvisation-water écrit la portée, les guides composent la mélodie, vous vous présentez avec les oreilles ouvertes.

Et lorsque quelqu'un vous dit “flottons un peu”, ne regardez pas votre montre. Vous êtes déjà là où vous vouliez aller.

Note de source : L'illustration du delta de l'Okavango dans votre PDF présente ce safari comme un “safari par l'eau”, menant à la région de l'Okavango. Réserve de Moremi et le plaisir surréaliste de éléphants nageursCes motifs et cette ambiance ancrent la voix narrative au-dessus..pdf)-compressed(1).pdf) [100_Dream_...ressed (1)]

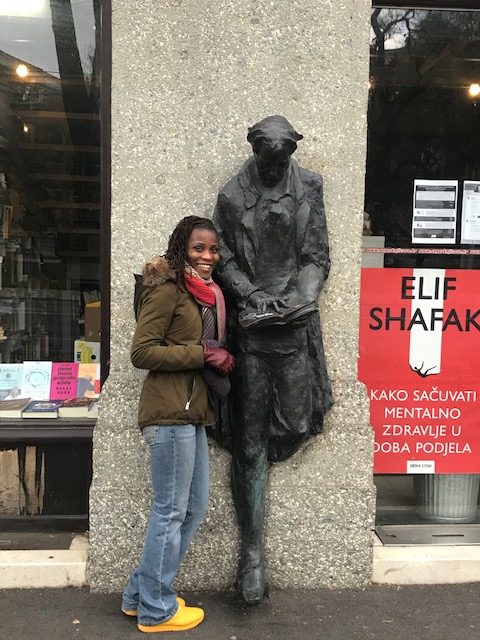

Écrit par Kariss

Plus de cette catégorie

Lac Victoria

Le voyage est souvent synonyme d'évasion, de rupture avec la routine, de voyage vers l'inconnu. Mais pour beaucoup, le voyage n'est pas une question de départ, c'est une question de retour. Retourner aux racines, aux histoires, aux lieux qui nous ont façonnés. Il s'agit de se reconnecter. La nageuse et écrivaine britannico-kényane Rebecca Achieng Ajulu-Bushell partage une réflexion profondément personnelle sur le lac Victoria, le plus grand lac tropical du monde et un lieu qui renferme l'histoire de sa famille, son identité et son premier amour : la natation.

Lac Victoria

Le voyage est souvent synonyme d'évasion, de rupture avec la routine, de voyage vers l'inconnu. Mais pour beaucoup, le voyage n'est pas une question de départ, c'est une question de retour. Retourner aux racines, aux histoires, aux lieux qui nous ont façonnés. Il s'agit de se reconnecter. La nageuse et écrivaine britannico-kényane Rebecca Achieng Ajulu-Bushell partage une réflexion profondément personnelle sur le lac Victoria, le plus grand lac tropical du monde et un lieu qui renferme l'histoire de sa famille, son identité et son premier amour : la natation.

Lac Victoria

Le voyage est souvent synonyme d'évasion, de rupture avec la routine, de voyage vers l'inconnu. Mais pour beaucoup, le voyage n'est pas une question de départ, c'est une question de retour. Retourner aux racines, aux histoires, aux lieux qui nous ont façonnés. Il s'agit de se reconnecter. La nageuse et écrivaine britannico-kényane Rebecca Achieng Ajulu-Bushell partage une réflexion profondément personnelle sur le lac Victoria, le plus grand lac tropical du monde et un lieu qui renferme l'histoire de sa famille, son identité et son premier amour : la natation.

0 Commentaires

Notre lettre d'information

0 commentaires