VICTORIA FALLS

Where the Zambezi Takes Flight

(Built around your document’s emphasis on the Falls as the “world’s largest sheet of falling water,” and the dare of Devil’s Pool.)-compressed%20(1).pdf) [100_Dream_…ressed (1)]

There is a sound the Zambezi makes just before it breaks its own heart.

A mile upstream of the Victoria Falls gorge, the river is wide and social, a slow procession with islands like shrugging shoulders and hippos doing their best submarine impressions in the reed beds. Then the lip arrives—a basalt edit mark—and the water becomes all decision: forward, down, everything. The world’s largest sheet of falling water isn’t just a fact you memorize; it’s a verb that happens to you.-compressed%20(1).pdf) [100_Dream_…ressed (1)]

I crossed the border twice with two passports tucked where I could feel them—a child’s talisman grown up. Zimbabwe first, for the path that stays in touch with spray, and Zambia for the dare that no sensible adult needs but somehow still wants: Devil’s Pool, that frothing nerve ending where the river lets you lean into the idea of falling and then, magnanimously, doesn’t let you..pdf)-compressed%20(1).pdf) [100_Dream_…ressed (1)]

Arrival: The Mist That Meant Everything

People told me the Lozi name—Mosi‑oa‑Tunya, the smoke that thunders—and I thought, lovely poetry, but it’s more like geology that learned to sing. From town, the plume looks like weather that grew impatient; up close, it’s a weather system with opinions. A tour guide named Simba (yes, and he rolled his eyes in advance of your joke) met me at the park gate and suggested we walk the path slowly. “People sprint and miss the skydive of it,” he said. “We will take the long way.”

We stepped onto a ribbon of trail snaking along the rim, and suddenly the world narrowed to spray and green. From one viewpoint the water sheered off the lip like a silk scarf being punished by a god; from another, the Falls looked combed, each column straight as a sermon. Rainbows half‑formed, broke, mended themselves. Cameras hiccuped under ponchos; laughter doubled back on itself in the mist.

The Zimbabwe Walk: The Gospel According to Spray

Simba knew where to stand so that the gorge’s rumble slid under your ribs and stayed. He named the viewpoints softy—Devil’s Cataract, Main Falls, Horseshoe, Rainbow—and I tried to hold each in its box but they kept spilling into one another. At the statue of David Livingstone, tourists gathered like polite grandchildren. “He didn’t discover the Falls,” Simba said, “he acquired them for a different story. But we still thank him for bringing the world’s eyes.” Then, a glance at the cliff across, where a line of people shrank themselves to the size of punctuation on a sentence of basalt. “Tomorrow, that’s you,” he said. “Don’t dream too long tonight.”

Night at the Edge: The Moon Rehearses the Sun

Dinner was at a lodge where someone had decided colonial style could be made gentler with good lighting. A marimba troupe played a song that made everyone’s elbows happy; a waiter taught me that Zambezi beer tastes better after you’ve applauded something. Later, I walked out onto the lawn and the gorge made its own case for insomnia. The Falls are never off. You go to sleep inside their breathing.

Border Handoff: Two Stamps, One River

Morning found me in a shuttle with strangers suddenly intimate enough to lend one another sunscreen. Zambia lay a bridge away, the air holding that pre‑storm shimmer it gets when every drop of water in a hundred‑mile radius seems to be writing its memoir. At Livingstone Island, our guide Myriam took one look at the group and sorted us into two piles—“squeal first, think later” and “think first, squeal later.” I tried to join the second but checked into the first somewhere between my second laugh and the river’s audible grin.

Devil’s Pool: The Edge Where You Remember Gravity is a Gift

Here is what happens at Devil’s Pool that doesn’t show up properly in the photos: your brain takes inventory of your bones and votes no; your body, lured by the guides’ competence and the sheer theater of the place, votes yes. You wade across a shallow tongue of river that thinks it’s a dare, clamber over a basalt ledge that thinks it’s a staircase, and then lower yourself into a cauldron that thinks it’s a joke. The lip is inches away. The river becomes your barber, giving you a spray shave from every angle. Someone takes your picture and you can see a rainbow trying to photobomb you.

“This is the part where you stop pretending you control everything,” Myriam said, one hand holding my ankle, the other pointing to a whirl the size of a small country. She counted, and we all whooped into the spray like it was a birthday wish. On the way back, the river hummed through the soles of my feet. I felt rinsed of the week, which had been a perfectly good week until the Zambezi edited it.

Back on the Zimbabwe Side: The Long Gaze

Later, I went back to the path and did it again, slower. This time I watched a swift hawk the gorge like it had rented it by the hour—flown into spray and out again, unbothered by physics. I stood at a spot where the Main Falls tore itself into veils and forgot that I had a checklist. A photographer handed me a lens cloth and performed the small miracle of making me see the same thing twice.

How the Falls Work Under Your Skin

In some places, you come for a single image—blue water and palmed beaches, a sand dune’s curve— and you leave with a reel. Victoria Falls grows scenes like a film that didn’t want to stop at feature length: the poncho laughter and the rainbow that insisted on being your shadow, the way people at the border recognized one another by the pattern of spray on their sleeves, the way even the shape of the gorge seems to keep saying “again” to the river. The word Mosi‑oa‑Tunya stops being a name and starts being a mood.

Practical Wisdom for a Good Ending

Two passports make the dance easier; your patience makes it beautiful. On the Zimbabwe side, give yourself the whole morning and a late lunch—step out for a tea and come back for another lap. On the Zambian side, respect the river’s calendar; Devil’s Pool is a seasonal privilege and the guides are your chorus of reason. Wear a hat you won’t mourn if the spray steals it; say yes to the poncho, no to bravado; and bring a lens cloth, because the Falls prefer every image to be half made of water.-compressed%20(1).pdf) [100_Dream_…ressed (1)]

Leaving: The Sound that Follows

When I finally sat on my bed with a towel halo and river hair, the roar stayed, tuned down to a household hum. Days later, on a flight over the Zambezi’s braided islands, I looked down and found the plume again. The plane banked and the Falls flashed, a sudden white mouth in a green face. I realized the river had taught me one of its tricks: how to take flight without leaving anything behind.

Source note: Your PDF casts the Falls as the largest sheet of falling water and calls out the dare of Devil’s Pool from the Zambian edge; the narrative above keeps both at center..pdf)-compressed%20(1).pdf) [100_Dream_…ressed (1)]

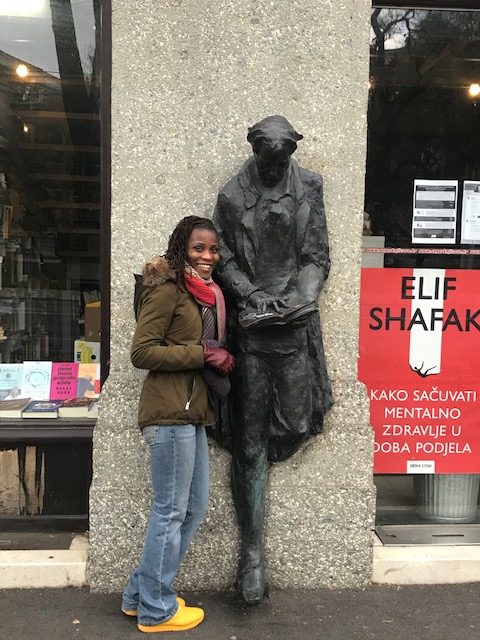

Written by Kariss

More From This Category

Lake Victoria

Travel is often framed as escape—a break from routine, a journey into the unknown. But for many, travel is not about leaving—it’s about returning. Returning to roots, to stories, to places that shaped us. It’s about reconnection. The British-Kenyan swimmer and writer Rebecca Achieng Ajulu-Bushell shares a deeply personal reflection on Lake Victoria, the largest tropical lake in the world and a place that holds her family’s history, her identity, and her first love—swimming.

Lake Victoria

Travel is often framed as escape—a break from routine, a journey into the unknown. But for many, travel is not about leaving—it’s about returning. Returning to roots, to stories, to places that shaped us. It’s about reconnection. The British-Kenyan swimmer and writer Rebecca Achieng Ajulu-Bushell shares a deeply personal reflection on Lake Victoria, the largest tropical lake in the world and a place that holds her family’s history, her identity, and her first love—swimming.

Lake Victoria

Travel is often framed as escape—a break from routine, a journey into the unknown. But for many, travel is not about leaving—it’s about returning. Returning to roots, to stories, to places that shaped us. It’s about reconnection. The British-Kenyan swimmer and writer Rebecca Achieng Ajulu-Bushell shares a deeply personal reflection on Lake Victoria, the largest tropical lake in the world and a place that holds her family’s history, her identity, and her first love—swimming.

0 Comments

Our Newsletter

0条评论